For a speechwriter, writing speeches is definitely easier than giving then – at least for me. I’ve penned my fair share of speeches, but I’ve only delivered a few, and very rarely in Japanese.

Giving a presentation in Japanese for Dentsu PR in Tokyo earlier this year was one of the most terrifying experiences of my life. If you’d been there, you would have seen the doctor getting a taste of his own medicine.

Nevertheless, I thought I’d share a few thoughts from my talk. The audience were mostly executives from the communications departments of Japanese companies. I tried to tap my own experience as a speechwriter for Nissan’s Executive Committee to help them prepare speeches for their own executives.

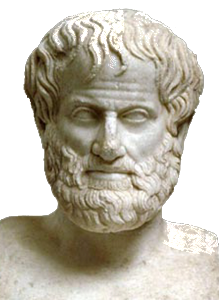

As I told them, there was only time to scratch the surface of this topic in my talk. After all, rhetoric is as old as Aristotle. But this is the internet, so here is a handy list of pointers!

1) A speech is “speech”, not writing

A little obvious, but when you give a speech you need to talk to people. You can’t just read out a press release and expect it to magically become a speech. Many of the techniques used by speechwriters, and most of the below, are all about the difference between writing and speaking.

2) Speak to the audience

Who’s the audience? Are you really talking to them? Even when the topic is the same. How would you speak to a group of employees or to a group of university students? Will they understand the jargon you use? Will they even be interested in the topic you’ve chosen?

3) Too many cooks . . .

This is a difficult one. Working one-to-one with the speech-giver is ideal for a speechwriter, but having to work with a communications dept cast of thousands in the preparation of a speech is far more usual. Still, worth saying.

4) Putting words in someone else’s mouth

How does your speaker speak? Are there some words and phrases they like? Are there some they stumble on? Listen to how they talk. (One of the reasons the preceding point is important). This is a particular issue when the speech is not in the speaker’s native language.

5) A beginning, a muddle, an end

This one goes for an writing too, but make sure the speech has a beginning, a muddle (I mean middle), and an end. There are many, many, effective ways to start and end speeches. The bit in the middle needs to be thought through carefully, and carefully ordered.

6) 2000-year-old tricks

Rhetoric. Rhetoric. Rhetoric. Are we not inheritors of a glorious tradition? (The rule of threes and the rhetorical question). They’ve been used for thousands of years and they still work!

7) Powerpoint is your enemy

This is a classic one for Japan. Maybe Japanese people are unusually visually-minded (blame kanji), or maybe they don’t like to speak, but it’s really hard to listen to a speech while trying to assimilate page upon page of Powerpoint. Match the visual materials to the speech. Not the other way around!

8) Success!

Congratulations speechwriter. You’ve written a great speech, and really spoke ‘to’ your audience. There and then. In front of them. That’s something you can’t do with the written word. Even on the Internet.